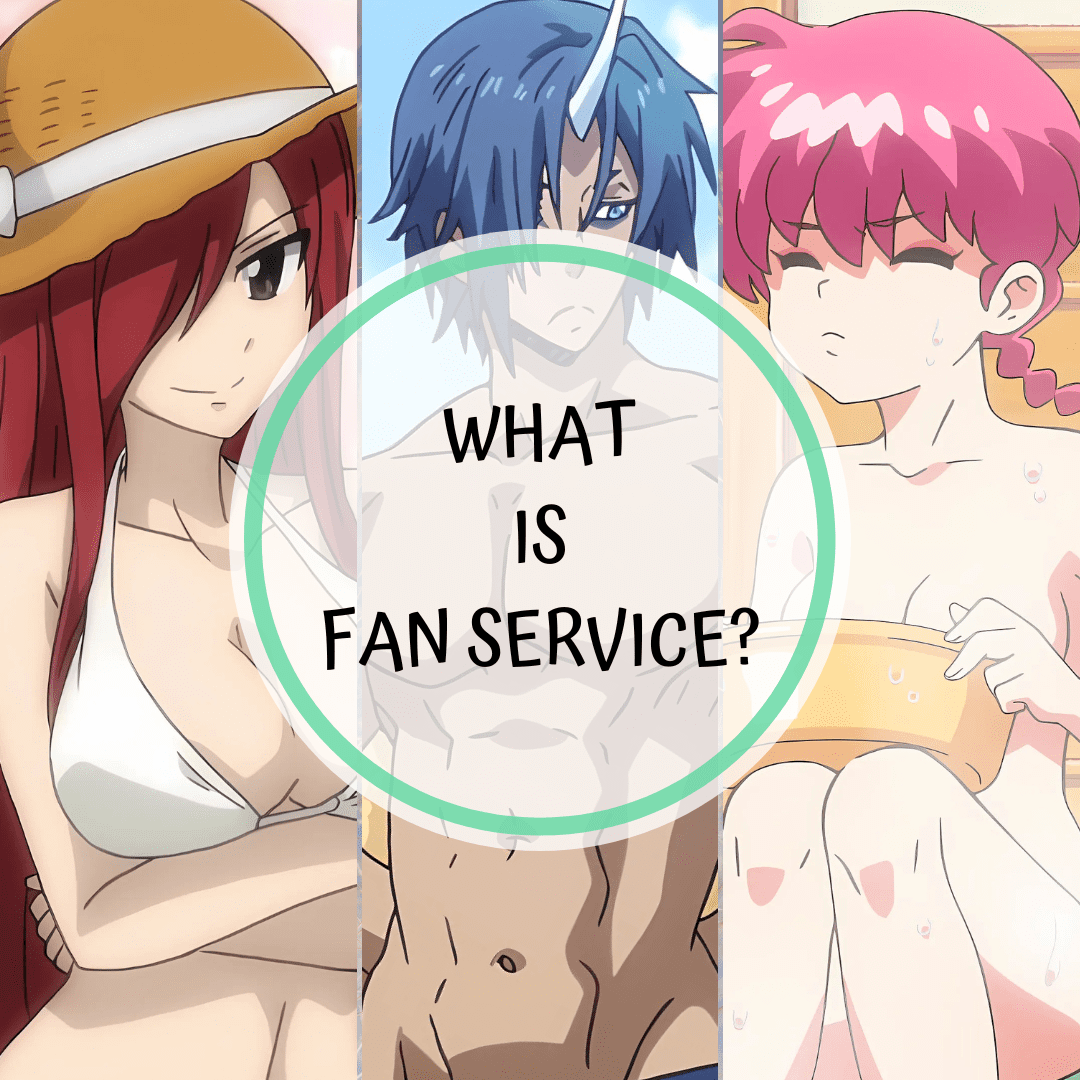

I recall the first time I noticed a “fan service” moment in anime, a seemingly random scene where the camera zoomed in on a character’s underwear for no plot-related reason, and I felt confused. Little did I know that such cheeky add-ons are part of a long tradition in anime and manga. If you’ve ever watched a show where a sudden swimsuit episode, a gratuitous wink at the camera, or a cameo of a beloved character made you smile (or blush), then you’ve experienced fan service. So, what exactly is fan service, and why is it such a mainstay in otaku culture? Let’s dive into this concept and break down everything from its hallmark tropes to its evolution over time.

Definition of Fan Service

Fan service, sometimes spelt as one word “fanservice,” refers to any material in a fictional work deliberately added just to please the audience. In practice, the term usually implies extra, non-essential moments that “service” the fans by giving them exactly what they want, often in the form of visual treats or callbacks. In anime and manga, fan service is very often sexual in nature (partial nudity, suggestive scenes, flirty humour), but it’s not limited to that. Essentially, it’s about indulging the audience: a wink and nod from creators to fans, sometimes literally.

It’s distinct from outright pornographic content. Fan service stays teasing or PG-13/R-rated at most, suggestive but not showing actual sex or genitalia. For example, a scene might show a female character’s clothes torn just enough to reveal skin or a male idol character stepping out of a shower with a towel hanging low, but they won’t show anything too graphic. The goal is titillation or excitement, not explicit depiction. In fact, the term fan service itself originated in the Japanese anime/manga fandom to describe these extra goodies for fans. When anime began being translated to English, many of these “service cuts” were edited out for being too risqué for Western TV, highlighting how fan service pushes right up to the cultural line of what’s acceptable.

Interestingly, outside Japan, the concept has broadened. These days, you might hear “fan service” used for any crowd-pleasing inclusion, not just sexy scenes. Easter eggs in a Marvel movie? A pop star sneaking references only die-hard fans understand? Those can also be considered fan service. However, for the purpose of this post, I’ll focus on fan service in anime/manga, where the term originated and where it often involves a playful mix of sexual innuendo, visual spectacle, and nods to the fans.

For a deeper dive into ecchi, check out my dedicated post here

Typical Content and Themes in Fan Service

When anime fans talk about fan service, they’re usually picturing a few instantly recognisable tropes (especially on the sexy side):

- Accidental pervert moments: e.g. a hapless protagonist trips and lands in a compromising position on a female character, cue blushing and a slapstick “Pervert!” reaction.

- Revealing outfits and “panty shots”: camera angles that flash a character’s underwear or emphasise cleavage and curves.

- Comedic nosebleeds & overreactions: characters (often male) get exaggerated nosebleeds, bugged-out eyes, or fainting spells to humorously signify arousal when fan service happens.

- Double entendres and suggestive dialogue: lines that sound innocent but hint at something lewd, just to get a chuckle out of viewers in the know.

A classic fan service scenario might involve, say, the main character walking in on someone changing or bathing by accident. Suddenly, you get strategically placed steam, rubber duck or beams of light covering the nude bits (censorship used as a gag) while everyone on screen screams in embarrassment. The scene adds nothing to the plot, but it does add a dose of teasing humour that the audience is in on. They are essentially “gratuitous displays” of fleeting glimpses, a quick glimpse of a panty flash here, a brief shot of a chest there, to catch the viewer off guard and let their imagination run wild. It’s all about the tease.

Some common sexual fan service includes:

- Beach episodes and hot spring visits: an entire episode where the cast goes to the beach or a Japanese onsen, giving a convenient excuse for swimsuit eye candy or towel-clad bath scenes.

- Wardrobe malfunctions or costume changes: during a battle or a slapstick gag, clothing gets ripped or falls off just so, or characters suddenly don fun outfits (e.g. maid costumes, cosplay) purely to delight fans.

- “Jiggle physics”: yes, the infamous breast bounce. Some studios animate exaggerated bouncing movements for female characters. (It’s even nicknamed the “Gainax bounce,” after the studio Gainax snuck eye-popping bounce animations into 1980s projects.)

- Lingerie and shower scenes: randomly cutting to a character in the shower or in revealing sleepwear, purely as pin-up material. (Shower and bath scenes were especially common in ’80s-’90s anime fan service.)

Anime scene of a clumsy boy tripping into a girl’s chest, resulting in comic embarrassment – a staple fan service gag.

While sexy visuals are front and centre in most discussions of fan service (indeed, “sexy fan service is considered the default form” because it’s what everyone remembers most), it’s important to note that fan service isn’t only about sex appeal. Any element that is primarily there to thrill fans rather than advance the story qualifies.

Some common non-sexual fan service includes:

- Cool action spectacle: e.g. extra-long mecha transformation sequences or fight scenes that exist mainly to show off gorgeous animation or badass moves. There’s no narrative need for a battle to last five episodes, but it looks cool, so it’s done to indulge fans of action.

- Cameos and call-backs: creators might bring back a popular character just for one episode or sneak in a surprise cameo of a character from a previous season/series. It might not make much sense plot-wise, but longtime fans squee with delight at seeing their favourite return.

- Easter eggs & meta-references: little background details or lines that reference other anime, games, or earlier episodes. These “inside jokes” reward devoted fans for paying attention (for example, a show might recreate a famous meme or reference a voice actor’s past role purely to get a rise out of the audience).

- “Pandering” character traits: even certain character designs or personalities can be fan service. For instance, including an ultra-cute catgirl solely because the audience loves catgirls, or giving a male hero absurdly chiselled abs just to draw cheers. These don’t directly push the plot, but they push the right buttons for fans.

In short, anything primarily there to make fans happy = fan service. Yes, that often means cheeky sexual moments because those get a big reaction, but it can also mean a flashy robot cameo or a romantic ship-tease between characters. Fan service is essentially the creators saying, “We know what you like, and here it is – enjoy!”

Form, Structure, and Style

How is fan service actually woven into an anime’s structure or visual style? In many cases, fan service is a sort of spice added to the usual recipe. Shows often follow a pattern where serious storytelling pauses for a moment of indulgence. For example, a tense action arc might suddenly give us a lighthearted beach episode to showcase characters in swimsuits (an almost ritualised break in tone), or a romance drama might toss in an onsen scene to get the leads into a steamy (if silly) situation together. These detours are usually self-contained: they start with a normal scenario, escalate into a risqué or over-the-top predicament, then end with everything back to status quo (often with a comedic punchline). In other words, fan service scenes seldom have lasting consequences – their purpose is the moment itself, not the impact on the story.

Visually, fan service-heavy scenes often do much of the comedic and dramatic lifting through exaggeration. Animators will gleefully highlight “assets”, think slow pan shots up a character’s body, camera angles from the floor gazing up (the better to glimpse those panties or boxer briefs). You’ll see over-the-top reactions too: faces turning tomato red, characters’ jaws dropping, or the infamous geyser-like nosebleed as a metaphor for arousal. The fourth wall might tremble a bit, characters sometimes complain aloud about pervy situations or obvious censors (acknowledging the absurdity). The tone is usually self-aware. The show is essentially winking at the viewer: “Yep, we know this is ridiculous, but we’re having fun with it – and we hope you are too.”

It’s also common for anime to have designated “fan service episodes” or segments, almost like specials. For instance, aside from obligatory beach/hot spring episodes, some series include bonus OVA episodes (often released on DVD) that ramp up the fan service since they’re free from TV broadcast rules. Even within a normal episode, a fan service bit might be cordoned off, such as a brief daydream sequence, a cosplay party scene, or a blink-and-you-miss-it pin-up shot thrown in during a transition. These moments are often tonally distinct from the main narrative (a serious sci-fi thriller might suddenly play goofy music during a random bath scene, signalling “don’t take this seriously, folks”). In terms of structure, then, fan service is usually a flourish on the side rather than the main course, except in shows that pride themselves on being built around fan service from the ground up.

Why It Works: Teasing and Pleasing the Audience

Why include fan service at all? Simply put, because it’s fun. Fan service thrives on a careful balance of tease and entertainment. In the case of sexy fan service, the appeal is in being naughty-but-not-too-naughty – it titillates the viewer just enough to get a reaction, often immediately followed by a joke to keep things light. You might blush one second and laugh the next. This one-two punch of “Ooh, did I just see that?!” and “Ha, of course that would happen!” keeps audiences engaged on a visceral level. It’s a playful dance between humour and heat. Whenever a scene risks becoming too steamy, a well-timed gag (like that comical slap or nosebleed) defuses the tension. And whenever things get too serious or monotonous, a bit of fan service spices things up and re-energises viewer attention.

Fan service also leverages a form of audience catharsis or payoff. Viewers become attached to characters and often want to see them in certain fun scenarios, be it romantic, sexy, or badass. Fan service delivers on those unspoken wishes. Are two characters flirting all series? A sudden close-to-kiss scene or suggestive accidental tumble might reward shippers who have been dying to see some spark. Love a show’s cool mechs? Here’s an extended transformation sequence with operatic music, just to make you go “heck yeah!” In essence, it’s about pleasing the base of fans who came for specific things. A little indulgence can greatly boost a show’s entertainment value and memorability.

That said, fan service is a double-edged sword. Used judiciously, it can make a show more popular and enjoyable; overused, it can pull viewers out of the story or even alienate them. A bit of cheesecake or beefcake can increase a show’s appeal, but too much fan service, or the wrong kind for the audience, can become distracting or off-putting. For example, if a normally serious anime suddenly shoves a gratuitous panty shot into a dramatic scene, viewers might roll their eyes or feel that it cheapens the moment. And what pleases one demographic might annoy another (someone not attracted to women might not appreciate a camera that constantly ogles female characters, and vice versa). Creators have to read the room: balance is key. When done right, though, fan service can be a major crowd-pleaser, sparking conversation, laughter, and yes, the occasional “did they really just do that?!” replay of a scene. Love it or hate it, those moments get people talking. And from the creators’ perspective, that means the show made an impact.

Some series even turn fan service into a kind of meta-commentary. A famous example is Kill la Kill, which piles on absurd levels of skimpy outfits and lewd humour on purpose, effectively satirising fan service by embracing it so hard. The audience is invited to laugh with the show at how ridiculous it all is, even as they secretly (or not so secretly) enjoy the spectacle. This self-awareness can make fan service feel more palatable, even clever. It’s as if the show is saying, “We know this is silly wish-fulfilment. Just roll with it and have a good time.” And honestly, that’s the core of why fan service works: it’s about having a good time. It appeals to basic human likes, attraction, nostalgia, and excitement in a straightforward way. Whenever a creator wants to stir those feelings in the audience quickly, fan service is a reliable tool.

It’s an age-old part of show business to give the people what they want, and in anime, what many fans want (at least some of the time) is exactly that extra dash of sexy, silly, or nostalgia-pandering fun.

Evolution of Fan Service Over Time

The beauty of fan service as a “genre element” is that it’s highly flexible. It can fuse with almost any story, provided the creators (and audience) are game for it. This means two series might both be heavy on fan service, yet feel completely different because one is “fan service + gothic horror” and the other is “fan service + slapstick school comedy.” Each context gives its own twist to the familiar tropes, e.g. a fantasy might justify skimpy armour with a spell, whereas a sci-fi might use a holodeck bikini simulation for downtime. This cross-pollination is how fan service stays continually interesting (or at least continually surprising!). It ensures that even if you think you’ve seen every panty shot setup or every clever Easter egg, the next anime will find a new spin on it.

Fan service rarely exists in isolation; it’s the extra flavour that, for better or worse, keeps fans wondering “What are they gonna throw at us next?” Love it, hate it, or tolerate it, fan service has become a universal language in pop culture, one that continues to evolve with each new generation of fans.

A Quick Timeline

1970s: Fan service in anime began treading into risqué territory by the early 1970s. A landmark example is Cutie Honey (1973), a shounen anime featuring the first-ever “nude transformation sequence” – when Honey transforms, there’s a brief nude silhouette. It was tame by today’s standards, but at the time, it was very cheeky. These early instances were often hidden in otherwise mainstream shows, giving viewers a surprising treat. The permissive, experimental vibe of late ‘60s–‘70s anime allowed creators to slip in a little sauciness and see how far they could go.

1980s: By the 1980s, fan service became much more common and overt in anime and manga. Full-frontal nudity, for instance, began appearing in certain manga and OVA (Original Video Animation) releases. Shower scenes and bathing shots became almost standard in many teen-oriented series; if you watch an ’80s anime, odds are there’s a random bath or locker room scene somewhere. Importantly, the 1980s saw the rise of the OVA market, which bypassed TV broadcast restrictions and allowed for racier content to be included for fans purchasing VHS tapes.

Meanwhile, in the West, such content was often censored or cut out due to stricter obscenity laws and rating systems. For example, when Japanese anime was localised, you’d sometimes find that bathing suit scenes were trimmed or risque costumes edited for audiences. Nonetheless, the fan service trend gained international traction through cult hits. A notable cross-cultural example: in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), Princess Leia’s famous “metal bikini” costume was very much a fan service move, an attempt to add sex appeal for (male) viewers in a blockbuster film. This showed that by the ’80s, not just anime but pop culture at large had come to understand the power of a well-placed sexy surprise.

1990s–2000s: Fan service truly solidified as a staple during the 1990s and early 2000s. This era gave us many dedicated ecchi and harem series where fan service was the selling point. For instance, the late ’90s OVA Agent Aika (1997) became infamous for its relentless up-skirt shots (practically every camera angle was chosen to show panties; it was like a self-aware parody of fan service). On the slightly more wholesome end, Love Hina (2000) popularised the harem rom-com formula: multiple girls, one guy, and countless comedic, sexy situations. Fans came to expect the hot spring episodes, culture festival cosplay scenes, and accidental groping gags in these shows. Even action-centric series started to sprinkle in more fan service, the original Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995) was a deep, psychological mecha anime, but it still managed to include plug-suit pin-up shots and a notorious scene of a teen boy falling on a girl’s chest (much to his terror).

In the manga world, To Love Ru (2006) pushed the boundary of what could run in a weekly shōnen magazine, with the creators openly admitting they tested the limits of acceptable ecchi content for teens. By the 2000s, late-night anime targeted at otaku were practically expected to deliver fan service to boost DVD sales. This period also coined terms like “Gainaxing” (for the Gainax bounce effect) and cemented tropes such as the obligatory pool episode, reflecting how ingrained these indulgences had become in anime conventions.

2010s: In the 2010s, fan service both exploded in variety and faced more scrutiny. Creators got creative in mixing fan service with other genres. We saw ecchi elements in unexpected places: a prime example is Food Wars! (Shokugeki no Soma), ostensibly a cooking competition anime, but famous for its foodgasm fan service (when characters taste delicious food, they hallucinate their clothes bursting off in metaphorical ecstasy). The isekai boom (protagonists transported to fantasy worlds) also embraced fan service; many such series feature harems or monster girls (e.g. Monster Musume) to keep things spicy in those magical realms.

Fan service for female audiences became more visible as well. The sports anime Free! (2013) garnered a huge female fanbase by focusing on “beefcake” fan service, tons of scenes with attractive boys swimming, stretching, and bonding shirtless, showing that fan service isn’t just for the guys anymore. At the same time, the 2010s saw an increase in self-aware parodies. Shimoneta (2015) lampooned a world of moral purity by being as lewd and absurd as possible, and Kill la Kill (2013) made a statement by blending empowering themes with over-the-top erotic imagery.

There was also a growing conversation in fan communities about when fan service goes too far (e.g. debates on whether certain scenes sexualise characters in an uncomfortable way). Some modern anime began toning down or localising fan service differently to reach broader audiences, but others doubled down, aiming squarely at the devoted fans who wanted it.

Today: Fan service is still thriving in the 2020s, and it has also gone truly global. The concept has permeated not only Japanese media but also entertainment worldwide. Big Hollywood franchises unabashedly employ “fan service moments”, think of all those surprise cameos, nostalgic references, or extra scenes in superhero movies purely included to make long-time fans cheer. In the music world, artists like Taylor Swift have been dubbed “masters of fan service” for hiding secret clues and inside references that only eagle-eyed fans will get.

In anime specifically, fan service continues to be a staple, though modern creators often try to strike a balance. New shows still give us the classic tropes (beach trips, costume parties, etc.), and some push boundaries further (for better or worse). Meanwhile, thanks to streaming and the internet, fan service-heavy content from other countries has gained exposure. The term “fan service” itself is now part of the global geek lexicon.

In Summary

Fan service is where entertainment indulges its audience with a knowing smile – be it through cheeky sexuality, nostalgic callbacks, or over-the-top spectacle. It’s the medium’s way of saying “we know what you like, and here’s a little extra just for you.” In anime, that often means making us laugh and blush in the same breath, weaving in saucy scenes or fun surprises that aren’t meant to be taken too seriously. From its early days of sneaking skirt flips and bikini armours, to the modern era of full-on self-parody and multi-genre mashups, fan service remains a beloved (if sometimes guilty) pleasure in the fandom.

At its heart, fan service is about joy, the simple joy of seeing something on screen that makes fans go “Yesss, I live for this!” Whether it’s a ridiculous harem comedy pratfall or a long-awaited cameo of your favourite character, those moments create a special connection between creators and the audience. They acknowledge that, beyond highbrow plot and artistry, part of the reason we watch is because it’s fun. And there’s nothing wrong with a bit of shameless fun. So the next time a completely unnecessary, over-the-top sexy (or cool, or cute) scene pops up in your anime, you can chuckle and say: “Ah, classic fan service… and I kinda love it.” After all, anime is a form of escapism, and what’s an escape without some extra treats along the way? In the end, fan service is an integral thread in the fabric of anime culture, one that continues to evolve with each new generation of fans but always with the same goal: to put a grin on our faces, whether through a blush, a laugh, or a cheer.

What type of fan service do you enjoy most?

All Sources: en.wikipedia 8news.qoo-app reddit japanpowered2 upload.wikimedia4 en.m.wikipedia crunchyroll imdb timesofi…ndiatimes gamefaqs.gamespot commons.wikimedia ricedigital.co medium

Leave a Reply